Majority Languages

Biblica owns and curates the NIV to ensure it keeps up with research and language changes. They aim to translate the Bible as accurately and idiomatically as a United Nations translator. For example, the NIV recently changed the word 'booty' to 'plunder', and 'aliens' to ‘landless immigrants’.

Biblica also supports

about a hundred translation committees in other languages. These committees work on Bibles in 'majority' languages - i.e., the languages

understood by the majority of people in the world. Those who speak minority

languages are usually bilingual - they have to be - because they also need to

know a majority language. So these majority languages are closer to being their

‘own’ language than a second language normally is.

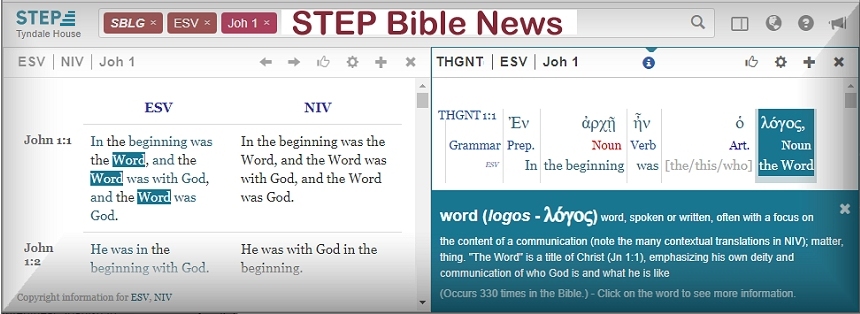

These translations now available in STEPBible, like the NIV, are written in a contemporary version of the language, without confusing out-of-date terminology. Often a strict word-to-word translation is useful when studying the underlying Hebrew or Greek. At other times it is useful to read a contemporary language translation that is straightforward to help to understand a Bible passage. STEPBible can show both types of Bibles side by side, with links to the original vocabulary they are translating, and tools to investigate them deeply.

The best of all Bible reading experiences is therefore now freely available in STEPBible. Everyone can read an easy-to-understand Bible in a majority language accessible to them, alongside translations that reflect word order and language traits of the underlying Hebrew and Greek. This mixture is the best way to read the Bible you love, and you can study words in depth when you come across something intriguing.

We would love to learn about how you are use STEPBible. Your feedback will help us to develop and enhance its capabilities. Please email STEPBibleATgmail with a note on how you use STEPBible. What ideas do you have to make STEPBible better? Do you know missionaries, church communities or others who would benefit from STEPBible? If you haven't already, please tell them about this resource. Would you like to help mature STEPBible? Let us know what you're good at. We particularly need help with translations of the interface into other languages.

Every

blessing

David

Instone-Brewer and the rest of the STEPBible team.

Try out the new Bibles at: www.STEPBible.org

New Amharic Standard Bible 2001

New Arabic Version 2012

Cebuano Contemporary

Bible 2014

Czech Living Bible 2012

Kurdish Sorani Standard Version 2020

Chinese Contemporary Bible (Simplified

Script) 2011

Chinese Contemporary Bible (Traditional

Script) 2012

The Bible in Everyday Danish 2015

Ewé Contemporary Version 2006

Gbagyi New Testament 1997

Hausa Contemporary New

Testament 2009

“The Way” Hebrew Living NT 2020

Hiligaynon Bible 2011

Hindi Contemporary Version 2019

The Book of Christ, in

Croatian 2000

Igbo Contemporary Bible, New

Testament 2019

Indonesian: Firman Allah Yang Hidup 2020

The Holy Word of God, in

Gikuyu, Kikuyu 2013

Korean Living Bible 1985

Luganda Contemporary

Bible 2019

Malayalam Contemporary

Version 2017

Ndebele Standard Bible 2006

New International Readers

Version 2014

New International Version 2011

New International Version, UK

spelling 2011

Het Boek, in Dutch, Flemish 2007

The Word of God, in Contemporary

Chichewa 2016

Persian Contemporary Bible, in

Farsi 2020

Polish Living New Testament 2016

Nova Versão Internacional, in

Brazilian Portuguese 2011

New Romanian Translation 2016

Central Asian Russian

Scriptures 2013

Central Asian Russian Scriptures (with

'Allah') 2013

Central Asian Russian Scriptures, in

Tajik 2013

New Russian Translation 2014

Slovenian Living New

Testament 2014

Shona Contemporary Bible 2018

Nueva Versión Internacional, in

Castilian Spanish 2017

Kiswahili Contemporary Version 2015

Tagalog Contemporary

Bible 2015

Thai New Contemporary Version 2007

The Word: Living Tswana New

Testament 1993

Akuapem Twi Contemporary Bible 2020 2020

Vietnamese Contemporary

Bible 2015

Kiyombe Contemporary Version 2002

Yoruba Contemporary Bible 2019